Sabu betrayed me.

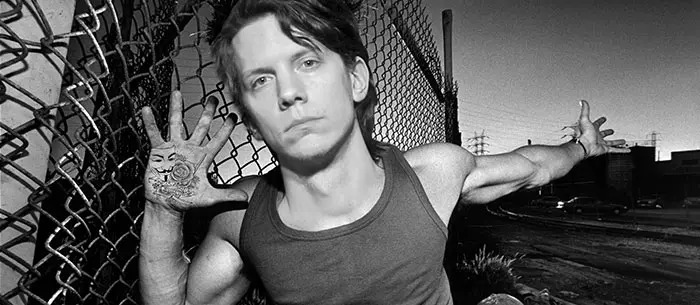

I’m an Anonymous hacker in prison, and I am not a crook. I’m an activist.

We may have hacked Sony back in the day, but we are still a social justice movement, from economic inequality to police brutality. Hacktivism is still the future.

Here in prison, I am asked a lot about hacking and especially about Anonymous, because of course there is interest in new technologies like Bitcoin for money or darknets for fraud. After all, convicts – like hackers – develop their own codes and ethics, and they are constantly finding ways to scam and exploit cracks in the system.

The anti-government message of Anonymous rings true among prisoners who have been railroaded, condemned and warehoused. So when they hear about hacked government websites and cops getting doxed, my fellow inmates often tell me things like, “It’s good to see people finally doing something about it.” That rejection of established, reformist avenues for achieving social change is why Anonymous continues as a force to be reckoned with, made all the more obvious by the presence of Guy Fawkes masks at the protests in Ferguson, Missouri – and beyond.

Hackers are a controversial, chaotic and commonly misunderstood bunch. Many of us have been arrested, from Mercedes Haefer and Andrew Auernheimer to Mustafa Al-Bassam and more, and few outside observers get that Anonymous is not a monolithic entity but a wide spectrum of backgrounds, politics and tactics. The journalist Barrett Brown gets it, but he continues to await his sentencing for merely linking to hacked material. And so I’ve been sharing a new book with my fellow inmates by the anthropologist and author Gabriella Coleman called Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous.

The book chronicles the development of Anonymous from its trickster troll days to its involvement in Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, to the LulzSec and AntiSec hacking sprees and all the word done by the group since Stratfor, the intelligence firm I hacked in 2012. But it is more than a timeline written by an outsider: Coleman spent years in dozens of chatrooms and travelled the world to meet hackers. Some, like my LulzSec codefendants in the UK, I have not heard from since our collaboration on various hacks and subsequent arrests, so I was especially happy to hear how they have been keeping the spirit alive.

Sabu betrayed me. How could we have been so foolish?

I was especially struck by Coleman’s interactions with Hector Monsegur – aka Sabu, the hacker-turned-FBI-informant who is responsible for many of our arrests and who was released this spring after his “extraordinary cooperation” with the FBI. One of the few people to ever meet him face-to-face until he gave an interview to Charlie Rose this month, Coleman had feelings that parallel my own: Sabu betrayed me.

Like everybody else, Coleman was convinced of Sabu’s street credibility because he talked tough and boasted about his access to ongoing hacking operations. Yes, I’m a natural-born leader, he would say. I can lead this entire movement on my own if I wanted to live like a dictator. What the fuck is up with all the snitches? Reading those and hundreds of other infuriating quotes in retrospect begs the question: How could we have been so foolish?

Sabu wasn’t doing much hacking himself, but he was in every chatroom. He was keeping tabs on upcoming hacks. He was running his mouth on Twitter to establish his self-appointed gatekeeper status. Coleman argues that this “hacker vanguardism” – relying on a select few to do all the attacks or act as spokesperson – detracted from the populist meritocracy of Anonymous and left us more vulnerable to infiltration and arrest.

Despite the “Sabutage”, the 2011 AntiSec phase of Anonymous – when a small but effective group of us took on everyone from Sony to Fox News – may have been the movement’s most active and effective period. At the height of Occupy Wall Street, Anons were gaining street protest experience and political maturity. The hacks were escalating in number and gravity, targeting symbols of economic inequality and police brutality, and in many ways Anonymous was becoming more decentralized, more open-source and tactically diverse enough to represented the future of hacktivism – and maybe even part of the future of activism.

Coleman’s book is not an unquestioned endorsement: we weren’t always legal, and we were often random, incoherent and politically incorrect. Still, most people who cover Anonymous get it wrong, and so they get trolled or hacked in the process. People like Sabu don’t get it, and anti-hacking prosecutors certainly don’t either.

We are condemned as criminals without consciences, dismissed as anti-social teens without a cause, or hyped as cyber-terrorists to justify the expanding surveillance state. But hacktivism exists within the history of social justice movements. Hacktivism is still the future, and it’s good to see people still doing something about it.

— By Jeremy Hammond (theguardian.com)